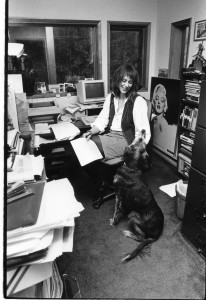

Marilyn Bowering on Poetry

Interview by Ajmer Rode, translator into Punjabi of Marilyn Bowering’s Calendar Poems.

http://www.ajmerrode.ca/

Creative Process

Q: How does a poem happen? Is inspiration necessary or do you just start writing it without any inspiration – like American poet Ashbury?

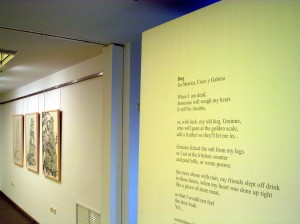

Usually the poem begins with a feeling: I can tell one is ‘there’ but I may not have any idea what it’s about. Often, too, it will begin with a line or phrase. Sometimes I’ll carry the line around for days until I can get to it. For instance, recently the phrase “When I used to dream” came into my mind. I’ve written that poem, but I also know–logically–because of the scope of the phrase–that there may be a number of other poems hidden behind it. I do think it’s quite possible to write as Ashbury does, as well. The act of writing, itself, can uncover waiting poems. I suppose that’s how I think of them: waiting for the right time, place and connection to come into being.

Q: How do you know when a poem is complete? Is a poem ever fully complete?

Yes, a poem is complete for what it is, although it’s true that sometimes I keep fiddling. I suppose you know the poem is complete when the form tells you so. A lot can be going on: the resolution of an image, the shape made by a poetic plot. It’s the same kind of question as how do you know when a song is over? It’s over when it’s over!

Q: Can writing of good poetry be learnt? How important is the craft, the use of poetic devices? Is metaphor still the backbone of poetry?

You can certainly be taught the craft of poetry if you’re willing to learn. To learn it, though–which isn’t easy and takes time and effort–you have to be determined and believe the effort will be worthwhile. Even when nobody else does! I think that ‘real’ poets undertake this training–I can’t think of a single significant poet who hasn’t spent years on craft. Most poets use poetic devices, although they may be hidden or disguised. Poets frequently use rhetorical devices or types of rhyme but in an ‘organic’ way so that the structures used aren’t obvious. An occasional pleasure of mine is to take a poem to pieces, to see what it’s made of–rather like taking apart a watch to see how it works. Of course what you end up with isn’t the poem: but it’s the aspect of the poem that’s responsible for density: the ‘poem’–it’s meaning and spirit–coalesces around the artifacts of structure.

Q: When you write do you have a particular audience in mind? If you do, does it affect your writing process? And do you think the reader has to be in a special mood to enjoy poetry?

Much of my poetry has to do with asking questions, although the poems are rarely framed that way. A question might be–as in the phrase I mentioned above, “When I used to dream–what is the difference between the past and the present and what does the absence of dream mean? This poem turned out to describe the ‘geography’ of that absence–to describe a country which I hope to explore further. In fact, I think that much poetry, for me, is a means of exploration–a tool with which to explore and reveal things I can’t get to any other way. Some poems do other things, of course–I’m also interested in character and persona and in the different things that can be said through different voices. If I write for an audience at all, it’s simply those who are curious, too–who marvel at the world and its variety and are willing to approach it through sound and beauty. I feel that the poems speak person to person–it’s a very close relationship, and quite different form what I feel about writing fiction. Fiction invites companionship; poetry speaks heart to heart or not at all!

I do think that the reader has to be in a certain frame of mind to enjoy poetry. There are times and circumstances in which I can’t read poetry at all. Then I’ll come upon something that expresses exactly what I’m feeling; or that opens up something new–and I’ll be caught.

Q: What do you think poetry essentially aims at? evoking emotional response in the reader, bringing new awareness, renewal of the language, or…?

The kind of emotional response a poem evokes is important. It has to be balanced with the thought process in the poem. The ideal poem does all three: it makes a connection to the reader in some new way which includes fresh use of language. I’m aware, sometimes, in writing poems of deliberately toning down one or the other of these aspects: it can be too easy to make gestures in a poem–for the language to be overly clever, or the emotion to be grandiose. Holding back can make for a better, more human poem.

Q: What does poetry mean to you? How does writing of a poem affect you?

The classical answer to the question, Why do you write poetry? is Because I must. It’s a compulsion, a need and a service; fundamentally, it’s a way to articulate life. Writing a poem makes me feel ‘normal’ – as if I’m in the right place at the right time doing the right thing; although I’d like to qualify that by saying that some poems feel ‘wrong’ and I write them to get them out of the way. I also feel humbled by poetry–its capacity for depth, humour, insight is so great, and mostly it feels like it has very little to do with ‘me’.

Marilyn’s Poetry

Q: Your poetry is often described as a blend of intellect and affection. How do you achieve it? Is such a blend necessary for poetry?

I really don’t see how poetry can ‘not’ be such a blend–although as soon as I say this I can think of exceptions. St. John Perse, for instance, can hardly be called ‘affectionate’, although poets I love from John Donne to Mona Van Dyn are, and in such different ways. It’s completely understandable why most people who don’t write poetry nevertheless associate it with love.

The underlying song of poetry is a love song–to an individual, or the world or the stars and planets. To life and death.

Q: Narrative form seems to dominate your poetry. In Alchemy of Happiness even your Calender poems describing the 12 months are little narratives while other poets have normally describe up or down moods associated with the months ( as for example American poet Linda Pastan has done in The Months in a 1999 issue of the POETRY magazine. Two Sikh Guru-poets, Nanak and Arjan, have written the most celebrated Calander poems in Punjabi drenched in spiritual love). Do you find the narrative form more expressive or more suited to what you want to say?

I’ve been writing poetry for a very long time. My poetry ‘career’ divides into before and after narrative. I published a number of books, culminating in a New and Selected collection, “The Sunday Before Winter” and then felt I’d come to the end of my interest in the single lyric poem.

Since this is around the same period when I began seriously to work on fiction, there may well be a connection, although I think I felt that all poems point to narrative anyway and that it was time I incorporated that ‘ripple’ into the work on the page. The Calendar poems incorporate, as you say, little stories; but there are also some short lyrics: I was thinking not so much about the movement of the months as what is memorable–how memory makes its own calendar out of event and feeling, anniversaries, co-incidence etc.

Q: You have written long poems on many historical Characters like Marilyn Monroe in Any One Can See I Love You, Soviet dog Laika in Calling All The World , George Sand and Chopin in Love As It Is… What inspires you to write on such characters?

There are different reasons for writing about each of these characters. One way or the other, they have all had personal impact on me, and have also–obviously–been important to culture at large. Writing Marilyn was initially a challenge from a BBC producer; I found, when I thought about it, that I had a strong emotional response to her because of sharing a first name: that she had helped to shape how *I* had been treated as a young girl and woman. All poetry is an act of empathy, but the Monroe work was particularly so in that I wanted the poems to be in her voice.

The poignancy of the space dog Laika–that exhilaration of sending a living creature into space combined with the fact that Laika couldn’t be brought back–had stayed with me since I was a child. Advance combined with sacrifice: it’s heroic, and an animal tale, and thus involves the innocent. For some reason I ‘heard’ this piece with Prokofiev’s music for the film Alexander Nevsky – which was used when the work was recorded for radio.

As for George Sand and Chopin: I was intrigued by a long letter she wrote to a friend of Chopin in which she outlined all the reasons why she should not allow herself to fall in love with him; and during which she argued herself into the affair. It’s a wonderful piece of head vs heart in which the heart wins.–and you can tell that the result will be messy. I wanted to try and catch the ‘under-voices’ I heard in both Sand’s and Chopin’s letters–as if beneath the surface something much more elemental was going on.

Q: In Poetics, Aristotle comments on the difference between history and poetry: “The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philsophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular?” Do you think Aristotle’s statement is still true? How do you create poetry out of history?

Poetry’s highest aim is to express the universal, and of course, this is attained through expression of the particular–which I think answers the question! On thinking over Aristotle’s statement, I wonder if he was talking in any way about prescience–a quality that poetry often has? Might this be because poets often work from dreams or other aspects of their sub and un conscious? Poets, musicians, painters all pick up things from the air, at times–this is easy to see retrospectively, and I find, sometimes, that a poem will anticipate an important personal experience. Sometimes I think that all art is a preparation. I don’t pretend to know for what; but the elements of beauty, and of musicality are important to me.

Poetry is created out of history or character through an empathic connection: you enter into it and bring it alive.

Q: Dead people figure frequently in your poems. They seem very much alive, sublime, joyful and… Do you see life and death as a continuum? Or your dead characters simply represent eternity of life?

The Alchemy of Happiness was written during a particular period of grief and it is certainly full of the dead. They do feel, to me, to be present and have things to say. I don’t at all mean that I see ghosts or anything like that: but my experience of loving someone when they die has surprised me: there is so much joy and interest there. Again, I don’t at all pretend to offer an interpretation–that’s not something I would want to do in poetry: the poems are really quite simple: they attempt to offer in a concrete way and as accurately as they can, particular experience. At the least, I suppose, they’re a map of my mind. It sometimes amazes me that people don’t ask more questions about what I write!

Canadian Poetry

Q: How would you describe the dominant type of mainstream Canadian poetry? How does it fare in the context of world poetry?

Is there a dominant mainstream type of Canadian poetry? I see such variety I wouldn’t know what to suggest as ‘mainstream.’ A change, certainly, is from landscape based work to urban-based; although I think a more interesting change is from regional to global. Of course (!) poetry is global; but Canadian poets seem more integrated into a world view than they once were–I’m thinking of the nationalistic phase when poets had to push hard to be published in Canada at all.

Instead of ‘types’ of poetry I think there are more ‘voices’: Anne Carson is very different from Karen Solie who is different from Margaret Atwood who is nothing like PK Page (although I recently read an article that suggested she had been influenced by PK’s imagery in her early work.) We seem to have worked through a period of ‘competency’–probably the result of workshops–that nearly killed poetry. Readers always, eventually, find real poetry.

Q: While West coast environment figures prominently in many BC poets, your poetry seems to go beyond such environment. How does geography influence, if it does, poetic imagination? comment?

My earlier work dealt very much with west coast environment. I’m thinking of the book, “The Killing Room” in particular, and before that a pamphlet, “One Who Became Lost” which contained many west coast poems. A cousin of mine recently returned from a ceremony in Toronto conducted by the Dalai Lama and explained to me that for the first three days the monks were basically asking the spirits of the place whether they could conduct the ritual on their territory. Geography influences how you write: it’s where you stand, where you move out from. In some way you have to ask permission of the environment, make your alliances with it, in order to be ‘grounded’. This is difficult, I think, in a country like Canada that has a post-colonial culture plunked on top of an aboriginal one. Where are the poet’s roots? Even the metaphor insists on a lineage to the soil. I feel very much freed, in my work, from having done that ground work (forgive the pun!) In fiction this operates a little differently: it’s as if no matter where the stories are situated, there’s always a path–often circuitous–that connects them to home.

Q: What do you think of writing ghazals in English? As you know in Canadian English poetry ghazal started in seventies perhaps with John Thompson. Then PK Page, Phyllis Web and others stepped in. Most recently Lorna Crozier has published a book of ghazals Bones in Their Wings. English ghazal has assumed a very different form than that written in Farsi, Urdu and Punjabi where the rhyme makes the backbone of the ghazal. English ghazal like most other forms of English poetry has discarded the rhyme. Do you think ghazal will make a come back in English? Could you comment on the importance of rhyme in poetry?

I’m not sure why many of these are being called ghazals at all. I don’t really see the point. Many of these, to my eye and ear, are simply images. I take it principally as a gesture–although why a gesture in the direction of ghazal–maybe an admission of something missing in current English language poetry?–I don’t really know.

Q: Can poetry really be translated? what is the importance of poetry translation in our multicultural and global world? What kind of poetry have you read through translation? Any experience with Indian or Chinese poetry? Have you been translated into other languages? Would you like to be translated into Punjabi?

I think poetry can be translated. The right translator is in harmony with the poems and with both languages. I love comparing translations as the differences bring out different nuances in the poems. I read a great deal of poetry in translation–mostly Spanish (which I can also read in the original), Russian, contemporary Chinese, Persian etc. My poems have been translated into Spanish. I would love to be translated into Punjabi–and also have some feedback as to how the poems ‘sound’ in that language: what resonance they find; how they fit (or don’t!)

Q: What do you think of what is called the mother tongue poetry being written in Canada in many languages? Forexample, take Punjabi. More than 100 poets live in British Columbia alone and they have published more than 300 books. Punjabi Writers Forum, still going strong, was founded in 1973 in Vancouver the year TWUC was founded. Yet majority of the Punjabi writers feel alienated in the national context. Although they contribute significantly to Canadian literature they lack government funding and recognition for their work. How would you address this issue?

The only way to address this is through translation–in editions, ideally, that are bilingual.

Education would help: for instance, information pamphlets distributed to Literary Festival Organisers so that they might include Punjabi writers in their programs?

Prizes

Q: You have been nominated for and won many prestigious prizes in poetry and fiction. What’s the importance of winning a prize for a writer? For you? How does it affect you?

We know that prizes are meaningless in the long run, but they have a practical effect: they make you more widely read and more visible–likely to be asked to give talks, readings, and even to write poems. We’re a little uncomfortable, in western society, with the public function of the poet–it tends to be ignored, or crushed into a little space–such as Canada’s new Poet Laureate experiment. We’re getting better at admitting poetry’s memorialising qualities into our culture–major tragedies, in particular, are likely to make the media turn to the poets for comprehension and a suitably meaningful response. But just as the rituals of most religions have lost meaning and function, so have the rituals of poetry. As long as poetry is just words and sounds and doesn’t act as an instrument to help open or keep open the heart and the world of intuitive intelligence–as long as its sense of purpose is lost–the acceptance of and readership for poetry will be small. Which is a circular way of saying that it’s more than a method of using language that’s endangered (in Western culture) it’s also a kind of intelligence that’s at risk. In my opinion.

Writing of poetry

Q: Any particular discipline needed for writing poetry? Is there a ‘best time’ for you to write poetry?

I used to set out on poetry projects–I even have one in mind–but mostly, now, I wait for the poem to come. If I weren’t writing fiction, as well, I’d be looking harder. The discipline is to not push the poem aside. Often, it seems, everything else takes priority over a poem (cooking, teaching, a hair-cut) but poetry is also an attitude: the wait isn’t passive; it’s an active listening for the shiver in the air that signals a poem. (‘Shiver’ isn’t quite right; but it does, to me, have a sensation.)

Q: Any suggestions for good poetry books? Suggestions for books on writing poetry? Anything new happening in poetics?

PK Pages and Philip Stratford’s “And Once More Saw The Stars”–a renga–introduced me to Stratford’s work which is amazing–technically fine and metaphysically playful (also dark). I’m currently reading Les Murray’s verse novel, Fredy Neptune.

Q: You are not in the category of old poets but from your experience with others tell us how do old poets live their lives? (eg Robin Skelton, Merriam Waddington) Do poets grow old at all? What makes a poet accept poverty rather than give up writing poetry?

Robin Skelton wrote, taught, published, translated until his death; Al Purdy finished a book shortly before he died; PK Page continues to write and publish wonderful poetry. Some poets seem to take on new life as they age–Elizabeth Brewster, for instance, who converted to Judaism when she was (roughly) eighty and then found she had many new things to say.. Poetry is a life; so poets simply continue with it–it’s not exactly something you retire from, although as all poets know, poetry can retire from you! I’m interested in this question as to why poets will do whatever they need to do to continue writing: the necessity of the poet is to write poems. Poets do not feel ‘whole’ unless they write; it’s a fundamental need. I’ve always felt this need as a drive to make shapes: there’s something almost geometrical–mathematical, anyway–about the perfection (this is an ideal) of the poem: it finds its shape, it has a shape, just as a crystal has a shape. Poetry is made of so many small things: syllables, words, sentences …images, sounds… and yet it achieves unity. Perhaps the desire to write poetry is a desire for completeness? Despite what much of the rest of the world appears to believe, the poet finds what he or she does useful. What is this utility? Sometimes, to celebrate beauty, but more often, I think, to suggest through the layers of the poem, that reality is similarly layered-maybe this is what we mean by saying poetry addresses universals